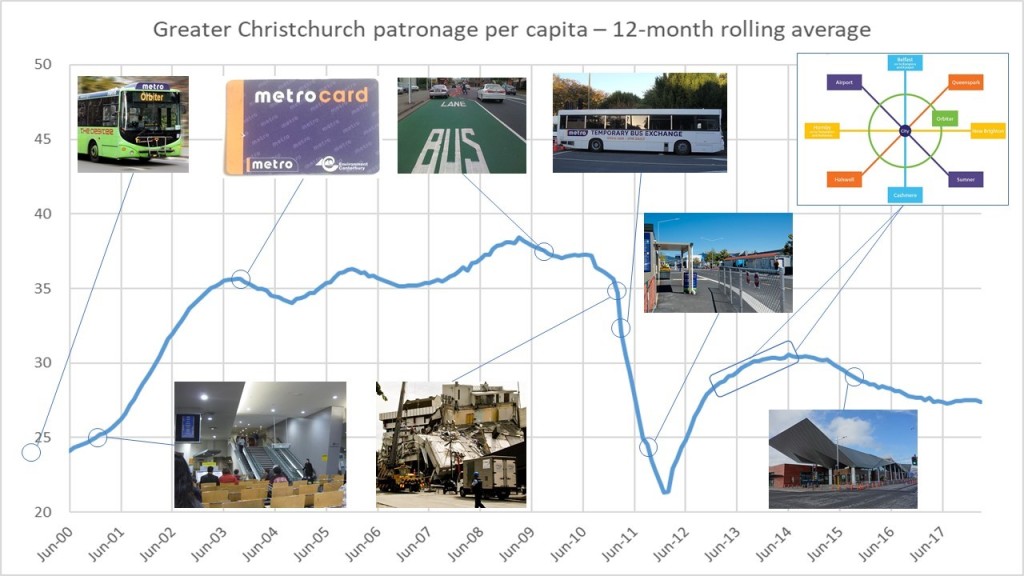

The Metrocard has been with us since October 2003 and it was introduced during a time when everything around public transport in Christchurch was looking positive and upwards. The Orbiter had been introduced in 1999; an immediate hit with the public. The Bus Exchange had opened in November 2000, replacing the windswept Square with an uber-modern central bus station that attracted many overseas delegations. When the Metrocard joined the mix of improvements, users got a discount for using this card over paying cash. Boarding times improved significantly as swiping a card is much faster than handling coins, making the bus journey quicker for all passengers. Those were the times when annual patronage per capita showed a healthy growth rate.

One significant event missing from the figure above is the fourteen elected regional councillors that were sacked by the Key government in March 2010 and replaced with seven commissioners. Under the pretence of an inability to resolve water management issues in Canterbury (by which was meant that farmers could not get further irrigation consents fast enough), the commissioners were put in place to implement policies that aligned with central government’s thinking. The transport minister of the day, Steven Joyce, displayed a transport planning understanding that did not extend much beyond “people want to drive” and one of his most damaging public transport initiatives was the introduction of the farebox recovery policy. This policy was adopted in April 2010 and set a goal of “of a national farebox recovery ratio of no less than 50 percent in the medium term”. In their general circular that was released by the Transport Agency at the time they stated that “we are not advocating short term measures that would have major impacts on patronage.” Cynics may read that to mean that major impacts on patronage are ok over the medium term. What is meant by farebox recovery is explained in a November 2009 post on what was then the TransportBlog. That the underlying thinking doesn’t make sense from a transport economics point of view was ably explained by Stu Donovan in August 2011.

The key policy document for individual regional councils is the Regional Public Transport Plan (RPTP) valid for 10 years and updated every three years. The 2010 RPTPs were due to be adopted by 1 July at the latest (and updated every three years thereafter), and as preparation plus consultation can easily take half a year the farebox recovery policy came too late to be incorporated into that main policy tool. The other policy tool is the Regional Land Transport Strategy (RLTS) and Auckland displayed active resistance through that document towards the fare recovery policy.

But no such problems in Canterbury, of course. With seven commissioners hand-picked by government in charge, anything can be achieved, right? In early February 2011 (i.e. before the main earthquake), the commissioners decreed that come April, new bus patrons would have to pay $10 for their initial Metrocard. From the beginning, there had always been a $10 replacement charge on the card, but the initial card had been free. ECan management’s argument that people would take more care with their Metrocard if they had to pay for it thus made no sense at all as any carelessness had always resulted in a $10 replacement fee. Rhys Taylor from the pedestrian lobby group Living Streets Aotearoa lamented that the decision “was made by a roomful of unelected car drivers” and while true, the commissioners simply implemented something that Steven Joyce wanted them to. After all, the initiative was estimated to save ECan’s ratepayers $85,000 per annum. None of the sacked councillors who commented at the time thought the initiative to be clever, though.

How much does an annual $85k saving represent? About 0.4% of ECan’s part of running public transport. Ok, that doesn’t sound like much, does it? What are the wider implications?

It’s hard to attract new customers to public transport. New Zealand has one of the highest car ownership rates in the world; car availability is high. Parking, apart from the core of the CBD, can generally be found for free. Thanks to the efforts by Christchurch City Council, cycling is becoming more attractive and feels increasingly safer. To use a bus, you first need to figure out where it leaves from and where it goes to. If time is important, it doesn’t help that on most routes the bus is significantly slower than driving. Figuring out when a bus leaves at a stop is also tricky as the advertised time generally refers to a location elsewhere; those with internet access have an easier task. Lastly, bus travel is perceived as expensive at $4 per zone 1 trip. That’s a lot of barriers to overcome to get somebody onto a bus for the first time.

But hang on, it’s only $2.65 with the Metrocard, isn’t it? That’s correct. Any marketing expert would advise that a good strategy for getting new clients for a product of low cost like a bus fare is to give something away; let people try it out. Charging for the initial Metrocard is doing the exact opposite to that good marketing strategy, as new customers who would like to try out a bus service without committing themselves to investing in a Metrocard pay a 50% penalty by paying with cash. It’s a textbook example of how not to organise your marketing approach.

And if the desire is to save $85k per annum, why not instead increase the price for replacement Metrocards instead? That would seem a much better approach as it does not disincentivise people from becoming customers in the first instance.

I’ve picked an obvious and reasonably simple to understand example of the consequences of the misguided fare recovery policy. The same policy was also a key driver for the hubs and spokes model that was rolled out from 2013 onward, although the earthquake impacts certainly contributed to the underlying thinking. The hubs and spokes model is the reason for an ongoing patronage decline in Christchurch. More clear-cut is the Wellington network restructure in July 2018 that was driven by the same desire to increase the fare recovery rate; the fallout from that has been in the news ever since.

ECan is currently consulting on the 2018–28 Canterbury Regional Public Transport Plan. Maybe let them know that charging for the initial Metrocard wasn’t such a good idea.

And one more thing about Metrocards – the other thing that was first introduced in April 2011 is Metrostickki. That’s a sticker with an embedded chip that provides the functionality of a Metrocard and one can attach it to the back of a mobile phone, say. As far as I know, the product has never been promoted. The only place where it is mentioned on the Metroinfo website is in the terms and conditions for using a Metrocard and it is left to Wikipedia to advertise its presence. It’s another curious approach to marketing.

Do you think it’s time to scrap the $10 Metrocard fee?

It’s surely a matter of time until contactless payment via debit cards becomes an option ?- we lived in London until last year and paying via credit card with daily caps was brilliant for me as a non-regular user. TfL seemed to love it too as it shifted all the payment administration to the banks.

For a returner to Christchurch – what did the bus route map look like prior to the hub/spoke rearrangement?

I’m really enjoying your work btw

LikeLike

Hello Wayne, yes, they are actively working on a contact-less debit system. Question is – how long will it take? And will it replace the Metrocard system? I suspect it won’t replace it; at least not initially. Hence asking for this to be thought about still makes sense.

Old network maps are in this blog post: https://chchtransport.wordpress.com/2012/02/14/network-maps/ The problem with the current hubs and spokes system is that the feeder services often have low frequencies (30 min or even 60 min headways) and there is little guarantee that you will make your connection (as the core line might be running late and there’s no system in place for making the feeder services wait for a late core route bus). Whilst hub and spokes looks much tidier on a map, it’s added quite some travel time for many, and a huge amount of uncertainty for most. Hence the declining patronage numbers.

LikeLike

There’s been discussion on the Auckland transport blog about credit card payment. (https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2018/07/09/hop-improvements-stopped/). I don’t knoe much about it but it sounds like they are going down that route there, in which case it’s probable it will end up here too. I had a look for an old network map but couldn’t find any… I think the general gist was that there were more routes, although fewer of them high-frequency routes (but still overall there were more service-kms).

LikeLike

Yes, the service kilometres were cut by about 10% and that was one of the main points of the exercise. Cut costs (to be more efficient) without losing patronage. The first part of the plan (cutting service kilometres) was never part of the official propaganda; this was always sold as a service improvement. Problem is that the second part of the plan did (to not lose patronage) didn’t work out like that. Maybe the service improvement part isn’t quite what has been achieved…

LikeLike

If you are doing a moving average of 12 months, you’ll have a phase-shift of exactly 6 months. I find it’s easier to graph it right, (ie, move by 6 months) then to explain to everyone why you didn’t do it right in the first place. 😉

LikeLike

Hi Synco, haven’t seen you in ages (a decade?). Hope all’s well. Still living next to the cemetery?

With regards to data smoothing, all I know is that it’s done (and without it, you can hardly make sense of the graph). I’ve never read up how to do it, but tried out a formula that made sense to me and it seemed to work just fine. If you know of a page or article that describes how it’s supposed to be done, could you post a link? Or PM me via Facebook.

LikeLike

Hi Axel,

Reason for the comment was my confusion, as I’ve seen many moving averages done badly, and the first couple of points you mention as ‘significant’ (sacked councillors, fairbox, …), these effects are not significant on the graph. After studying your graph longer, it made more sense yet would suggest you add the real data trace so the effect of filtering can be seen.

/s

LikeLike

There have been promotions where free cards were given away, but the other silly obstacle which I have always opposed is Metro’s insistence that cards have to be validated before they can be used. This means people have to make a special trip into the exchange with identification before they can use the card.

LikeLike

I don’t understand, Patrick. You can buy the Metrocard at a limited number of physical locations, and at any of those, you can show your ID upon purchase. There is thus no need to head into the Exchange. You can’t buy the Metrocard online. What am I missing?

http://www.metroinfo.co.nz/metrocard/Pages/WhereToBuy.aspx

LikeLike

Really interesting history here. $85k it’s such a tiny figure, especially considering the marginal riders that a $10 charge keeps away would probably bump farebox recovery a bit, if that was the aim.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The reason given on Greater Auckland for why our HOP cards cost $10 is that you can tag on with a very low credit and can go into negative. Apparently if you don’t have the $10 price tag, people deliberately put their cards into debit and then throw them away.

But in Christchurch, I imagine the cards can’t go into negative. Is that right? You tell the bus driver at the beginning how many zones to charge, and it gets deducted then. Plus, your cards have to be registered to an owner (ours don’t) so a debit could be transferred to any new card purchased by that owner anyway? So I think an appropriate cost in your case would be about $2.

I agree with the stupidity of the farebox recovery target and of the disincentive to trying public transport that either a high cash fare or the upfront card cost and hassle. Particularly if you’re travelling with a few children, the cost of the journey for everyone is a shock to the system.

LikeLike

I think you can slightly go into ‘overdraft’ on the Christchurch system. But I’m not entirely sure and it’s not discussed in the terms and conditions.

LikeLike

I think if your MetroCard bus fare takes into a negative balance they have no problem. If it’s already negative you can’t use it again until topped up (auto-topups when balance falls low is a great innovation!).

LikeLike

From an equity point of view PT cards should not be charged for. In the first instance and as its main objective PT “Public” transport is there to provide transport access and mobility to those that don’t have alternative transport means.

Charging for PT cards just adds to the barriers. Let ratepayers subsidise the cards.

LikeLiked by 1 person