If you can spare me a minute or two of your time, I’d like to talk about how many dollars that time is worth to you.

Deep within the hidden machinations that is transport decision making in New Zealand, there is a tiny little cog that turns a lot of very big levers. It’s a big part of the reason our cities look the way they do, why we have built lots of certain types infrastructure but very little of others, and why so many people will die on our roads in the coming years while we willingly choose not to do the things that we know would save them.

I’m talking about travel time values.

Many have written before about the headaches travel time values cause us. Ian Munro wrote a nice article here, NZTA have done several pieces of research into it including this one, Greater Auckland have written several pieces on it including this one. One I thought was especially on the money is Paul Buchanan’s paper on it here – in fact if you’ve only got a few minutes I’d recommend skipping my blog and just reading his paper instead.

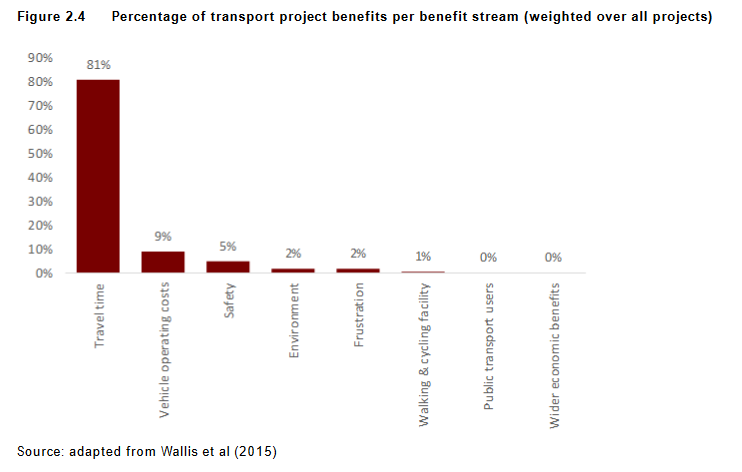

Travel time values are important as, in our current economic analysis framework, they make up by far the biggest benefits of our transport projects.

I got thinking about this the other day while I was reading some recent research the Transport Agency has commissioned to work out the value of travel time savings.

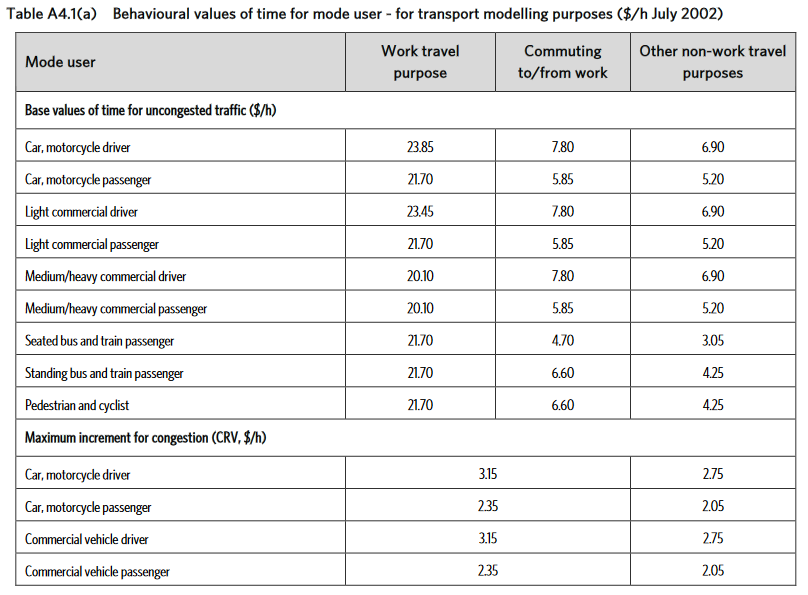

The work itself is fine, it answers the question it was supposed to answer. But reading the report it struck me how overly-simplistic the question being asked is. It basically asked “how do we figure out what dollar value people put on their travel time?”. The current Transport Agency Economic Evaluation Manual has a bunch of values below. They are split out into 3 purposes, different vehicle types, and even whether you are sitting down or standing up. So for example, if building a new road was going to save one car driver one hour driving to work, then that would be considered to add $7.80 of benefits to society.

The piece of research developed a survey that asked a series of questions to basically determine updated values for these travel time values, as these ones are a few years old now.

These factors are then used to determine which projects get built, and how transport systems then get operated. If building a new road saves lots of people lots of travel time, then it has a good chance of getting built, if it doesn’t then it doesn’t. If phasing traffic signals a certain way saves lots of people lots of time then it has a good chance of getting done, if it doesn’t then it doesn’t.

On the surface this sort of makes sense. But think about it for more than about 10 seconds and it quickly starts to seem way too simplistic. The way people value their time is very complex. If you’re rushing to the hospital with your wife in labour, you are probably going to be valuing your travel time extremely highly (i.e. you’ll be willing to pay a few dollars to get there a little quicker). But when you’re driving back home afterwards, you’ll probably be taking your time and not be too bothered how long the trip takes. Even the same trip on different days can have a very different value – some days I’m late for work and desperate to get there as quick as I can, other days I’m a little early and am not bothered if I get delayed for a few minutes for some reason. Every single trip on our transport system has a different value to the person making it.

In a free market this variation sorts itself out through pricing. For example a plane ticket on a certain route at a certain time has a certain price. If you’re willing to pay that then you can make that trip, if you’re not then you can’t. There are a massive range in prices from extremely cheap if you’re willing to fly at unpopular times or unpopular routes, to extremely expensive if you want to fly at the highest-demand time. So people choose their time and route based on the prices and how important it is to them personally to make that trip.

But our roads are different. We have only extremely blunt pricing (basically just rates and fuel excise). As a result there are currently lots of trips being made on our roads that are not actually of high value to the people making them. And because people making these trips are clogging up the roads, the trips that are genuinely important can’t get made properly.

There’s only really one proper solution to this – road pricing. This will almost certainly happen in time and will change everything about the way we plan and build our cities.

But even road pricing doesn’t really fix our problem of thinking about travel time values in an overly-simplistic way. We’re still going to need models of transport sytems, and still going to need to be able to predict if an idea for a project is any good or not.

I think a good start would be to treat travel times as a distribution rather than a blanket value, and incorporating this into the economic evaluation process. This would mean assuming travel times are distributed in some sort of bell curve from very low values, to very high values, and everything in between. When demand for roadspace exceeds supply (i.e. when there is congestion) it can be assumed that the trips that don’t get made are the very lowest value ones. If a project is being built to increase the capacity of the road system, and hence induce some of this suppressed demand back onto the roads, these trips should only be assessed at a much lower travel time value, not the same value as all the other trips currently being made. This would provide a more realistic (lower) estimate of the true value of road capacity increase projects.

This wouldn’t solve everything wrong with our transport decision making process, but it would at least remove one of the biggest, most obvious biases inherent in the current methodology.

Nice work, Chris! I also shared some thoughts on travel time values the other year: https://viastrada.nz/safe-efficient

LikeLike

Nice presentation Axel.

1) NZ needs a new nationwide design standard for transport infrastructure based on a vision zero approach from subdivision to state highway. This will reduce the crash rate on new infrastructure.

It should include items like providing sufficient space for all modes (eg fully protected cycle/scooter ways), approach based phasing at traffic signals with protected movements for all modes etc etc

2) Existing infrastructure should be ranked by the social cost of crashes and the worst sites/routes required to be bought up to the new design standard.

LikeLike

Thanks! Are we going to see you back in Christchurch at some point? I mean permanently?

LikeLike

Interesting presentation Axel. I’ve worked on a myriad of projects where we know exactly what we need to do to save lives, but are not able to due do them because they would cause too much delays so don’t get a postive BCR. I liked your calculation that the current EEM methodology equates 1 death every 14 years with 20,000 daily users saving 12 seconds on their commutes. I don’t think this reflects society’s real values.

I’m not sure we actually need to completely remove travel time from our economics though. I think we can just hike up the value we place on saving lives to an amount that more realistically reflects society’s values (and probably reduce travel time values too).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve watched the first few minutes and it looks intriguing Axel. Will watch the rest when I get a chance.

LikeLike

My preference is not for removing travel times per se. But I’m also not fond of simply playing around with values. From an ethical perspective, that seems wrong as we are still trading time and people’s safety. I’d rather have a hierarchical approach. Firstly, make things as safe as possible. Once that’s been worked out, make secondly use of travel time considerations to work out the best-performing option (if there are options). That prioritises safety over efficiency, and seems morally the right way to go about it.

LikeLike

The Buchanen paper was excellent thanks Chris. It clearly explained the different economics in play between rail and road led land use.

By my calculations in Christchurch if we keep building road only accessible suburbs then for every 10,000 house built 7.5sqkm land will be needed.

If we build 10,000 houses around train stations then only 1.5sqkm is needed.

Currently Greater Christchurch is building about 4000 houses a year, of which 3000 is greenfield and 1000 is infill housing.

So these sort of choices are very important.

Another factor is Greater Christchurch will get 10,000 KiwiBuild homes over the next decade where should they be built?

If Christchurch did build high density housing around congestion free rapid transit transport services. Then their would be two competing land use models.

Automobile only accessible suburbs that encourages dispersion of housing, jobs and land use. And rail based development that encourages concentration of housing, jobs and land use. Ideally there would be competitive tension between these land use options.

To keep the playing field even between the choices road pricing and removing car parking minimums would be required.

Japan has shown that when these hidden land use subsidies for automobiles are removed then rail based development can be very successfully delivered without subsidy.

LikeLike

Christchurch definitely needs more housing choice. It would be really interesting to see the demand for dense living on high quality public transport routes. I suspect it’s quite high, but it’s impossible to know for sure because we don’t have any at the moment.

LikeLike

Thanks, Chris. The different values ascribed to different users is pretty comical. There’s nowhere in this 81% reliance on travel times that a society can say, “Hey, it matters more that we have a clean beach to travel TO, without awful road runoff, than that we get there quickly.” As just one example.

This is probably the most important thing for the government to change right now. The road building that is occurring is only occurring because of poor land and transport modelling using incorrect calculations of travel time feeding the business cases.

And this road building induces traffic to the extent that it is undermining all the improvements intended to improve safety, access and environmental outcomes. So it’s working against other projects, meaning as rate and tax payers we are paying twice to get nowhere. And that affects value-for-money badly.

This reliance on travel time calculations – which they do so very badly – is entirely undoing the Government Policy Statement on Transport, which puts Safety, Access, Environment and Value-For-Money as the key priorities.

There’s a very clear step that needs to be taken now. And I’d throw the traffic modellers out at the same time. It is not professional to be using archaic models and advising their misuse.

The models themselves could be useful to provide a ‘snapshot in time’ of traffic with a certain network. But the inaccuracies in the models mean they should never be used to compare different scenarios, and it is in comparing them that they come up with such poor travel time saving estimates. This must stop.

LikeLike

The table does seem a little strange to me. In some areas it gets really specific, despite it being fundamentally an extremely blunt generalisation. Personally I don’t know that we should go that far, I think models and economics have their uses. I’d rather they were refined and improved than thrown out altogether. I think in general our economic methodology is really useful for comparing options that are quite similar, to work out which is the better option, e.g. one motorway alignment with another slightly different motorway alignment. But it’s not great at comparing completely different options, e.g. building a motorway versus building a train line.

LikeLike

While there are clearly issues with how travel times are valued, it is important to appreciate that it is not as important a factor as in the past because:

(1) the BCR is not often the determining factor in whether a project gets funded (many projects, deemed “low cost, low risk” (<$1m) or NZTA's new "pre-approved solutions" don't even need a BCR to be evaluated if they meet other strategic goals or background criteria; you just put them up and they get funded)

(2) For some projects now, you don't have to consider travel times. E.g. if it is a pedestrian crossing safety project then typically vehicle delay isn't a factor included in the BCR now. If a speed management project gets speeds down closer to the calculated "safe & acceptable speed" then that is a plus not a minus.

In practice now, BCRs only tend to be the tie-breaker once you have already assessed projects as falling into a "very-high/high/medium/low" priority category (eg the new Govt is tending to classify a lot of road safety and sustainable transport projects as high/very-high). So a "medium" priority project with BCR of 5 will probably be done before a "medium" project with BCR of 4, but a "high" priority project with BCR of 3 will beat both of them.

BTW, it is interesting that the values of travel time by different modes are all very similar now; they used to be quite different, with PT and active mode values being lower. Many people got their nose out of joint thinking that PT and active users weren't being valued as "important" as car users. Actually the values were reflecting the lost COST of that time: on a bus or train you could still read, check emails or some other productive activity; while walking or biking you are also getting some exercise. So in both cases, the time travelled is not as "wasted" as when you are stuck in a car having to (in theory) concentrate on driving…

LikeLike

1) Valuing non business travel time at below congested levels greatly concerns me.

We choose where we live and go shopping etc, how much we get paid (i.e what job we take) based on our knowledge of the inherent travel times related to that choice. Thus we treat the travel time cost as a sunk cost. One could argue on that basis we should apply 0 value to travel time savings below congested levels. As Axel points out in the presentation why should we put a benefit on saving 20,000 drivers 12 seconds each (assuming its non congested)

2) This is more safety related, but we apply more value to safety in aviation than we do in road safety. Its ok to kill 379 people on the roads in a year, but there would be an uproar if we killed that many in aviation crashes.

Much of this has to do with the minimum design/operating standards applied in roading (they are so so much lower) and thus travel time savings are easily able to outweigh design requirements.

3) The easiest way around the travel time issue is require vision zero design standards, i.e. apply the same requirements to roading as we expect from aviation. (this is also noted in my response to Axel above)

LikeLike

Another thought,

At least from a financial perspective (but not necessarily an complete economic one) the congestion toll levels in a place like Singapore should give an indication of the real financial value of time people perceive.

At an equilibrium toll level (and assuming network is operating D optimally just below congestion) the value of the toll should match the:

a) the average marginal travel time saving for a unit user to move back to car & pay the toll, and

b) visa versa, the average marginal additional travel time a unit user would face by not paying the toll.

From an average perspective the total toll revenue / total congestion time before tolls (assuming none after) should also reflect an average financial value of time.

LikeLike

1) I think you’re spot on with this. The Buchanan paper I link to goes into this in more detail. When you build a motorway that saves drivers 10 minutes each, people don’t just continue living in the same houses and working in the same workplaces and saving 10 minutes, in reality a lot shift further away and retain the same travel time as before. Indicating that that travel time saving isn’t actually particularly valuable to them.

a) The few toll roads we have are all carrying fewer people than was predicted, which I think is a global trend (certainly is true in Aussie). This might indicate that the travel time values we use are too high.

LikeLike

Great post. It’s interesting to think about the recent inner city speed changes from 50km/h to 30km/h and the controversy that has ensued (and still does wherever these changes are proposed). It boggles my mind that someone would value the minuscule time savings lost over such short distances, and in an inner-city area that they shouldn’t really be traversing as a through-route, when it undoubtedly provides many safety benefits for other road users and pedestrians.

Whilst I consider those changes a small win, I guess that the controversy serves to illustrate the wider issue of trying to foment wider change in NZ transport decision making processes. There is an interesting post on Greater Auckland today about induced demand and I thought it aligned with your post quite well and also illustrated how people gravitate to solutions that sound good at a high level (i.e. increase capacity to fit more cars in – duh) rather than acknowledge or seek to understand the nuances that could lead to other, better solutions.

LikeLike

Was there ever a BCR calculated for the 50 to 30kmh change do you know? I wonder how the EEM would handle that. Would also be interesting to see if an open road change from 100 to 80kmh would have a BCR over 1 using our current values. If ont, it would be interesting to reverse engineer it and see how far our values would need to change for it to be over 1.

LikeLike

I’m not sure if a BCR was done for that, but it would be interesting to see if it is out there.

I imagine the EEM would burst into flames…

LikeLike

The way it’s supposed to be done is to use the “safe and appropriate speed” as per the Speed Management Guide. That’s available from a database that’s not public; developed by the Transport Agency and shared with Road Controlling Authorities. So if you drop a speed limit to the “safe and appropriate speed” (or above), you aren’t supposed to be taking increased travel time into account. Bit of a roundabout way of going about this and this could still discourage safety work to be carried out, but at least it’s a step in the right direction.

LikeLike

Effectively the new process is rewarding you for getting speeds closer to the calculated safe and appropriate speed, rather than penalising you for slowing people down as was done previously. Personally, it seems like a neat solution, as over 80% of NZ roads currently have speed limits above their SAA Spd, which means that few sites will be penalised for speed management work.

LikeLike

I suggested a similar reverse engineering idea in my submission on the IAF – I’m not convinced the evaluation process has combined the priority rating with the BCR value well.

LikeLike

Food for thought

Click to access 702060ESW0P1200s0in0Urban0Transport.pdf

GOING BEYOND TRAVEL-TIME SAVINGS

This paper challenges the widespread and often indiscriminant use of travel time savings as a principal metric of economic benefits for evaluating urban transport projects. Time-budget theory and empirical evidence reveals that the benefits of a widened road or extended rail line often get expressed by more and longer trips to larger numbers of destinations and not by less time spent traveling.

National surveys in the UK show that travel hours per person per year remained constant from 1970 to 2005 (around 350-380 hours), a period of massive motorway construction throughout the British Isles.

According to Metz (2008), this implies “a long run value of travel time savings of zero”. What is preferred is more and longer trips – average distance travelled shot up by 60% over the 1970-2005 period.

LikeLike

To which the economists reply “thats true but the gain in utility from shifting outwards (cheaper land, bigger house etc) is roughly approximated by the benefit we calculated for travel time”.

LikeLike

Nice rad. Good article

LikeLike